Issues of political influence on port security are raised in this The New York Observer piece:

Imagine: a big cargo ship runs aground trying to get through a narrow channel between Staten Island and New Jersey on its way to Port Elizabeth. It tears its hull and cannot make it to the shipyard for repairs because it is sitting low in the water and there is no other route to New Jersey.Nice snark about spell check, too.

Such is the condition of New York Harbor--narrow channels, shallow waters, what were they thinking when they made this place a maritime center?--that such an event really happened, last Saturday morning. For a few hours, it blocked traffic. Then last night, the vessel made its way over to Red Hook's Pier 10, to the only container port in the New York area that did not require use of that channel. Where else could it have gone?

Baltimore.

American Stevedoring, the Red Hook port operator, and Rep. Jerrold Nadler, the port's chief cheerleader, staged a press conference today in front of the ship as it was unloading. It was a brilliant p.r. move meant to dramatize the possible consequences of Bloomberg's push to replace cargo ships with cruise ships in Brooklyn: What if a terrorist sunk a ship in Kill Van Kull and it refused to budge? Where would we get our food, our clothing, our bottled water?

Different sort of play in the Daily Mail coverage of Rep Nadler's PR op:

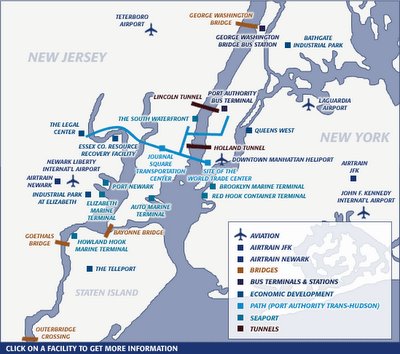

A freighter that got stuck in a shallow New Jersey shipping channel has been taken to the Red Hook port for unloading - a move critics say shows why the city shouldn't close Brooklyn's last working port.UPDATE; Added map of NY/NJ Port Authority sites from here.

"The city depends for its safety and security on maintaining a port in Brooklyn," said Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-Brooklyn), a longtime supporter of shipping in Brooklyn.

The Port Authority won't renew the lease of American Stevedoring, which runs the Red Hook Container Terminal, when it expires next April.

Nadler said yesterday the grounded freighter shows how vulnerable ships are in the Kill Van Kull, a narrow channel between New Jersey and Staten Island leading to the area's major ports.

Nadler said a large-scale accident - or a terrorist attack - in the "treacherous, shallow" channel could cripple the region's economy.

"In the event a large ship were to sink in the Kill Van Kull, most of our port would be closed for weeks or even months, and with it, New York City's import supply chain," Nadler said.

He said waters off Brooklyn are about 100 to 150 feet deep, while off New Jersey they are only 35 feet deep, though officials are in the midst of a $2 billion project to deepen the New Jersey channel to 50 feet, he said.

Port Authority spokesman Pasquale DiFulco called Nadler's argument "disingenuous at best." DiFulco said the Port Authority works closely with the Coast Guard on security at the Kill Van Kull. If something were to happen, the 90-acre Red Hook site is far too small to handle ships from New Jersey ports, he said.

Houston Chronicle notes that the Houston Ship Channel chemical plants are of concern:

In the Houston area, where sprawling chemical facilities along the Ship Channel are intermingled with parks and private homes, plant security would seem to have special relevance. Houston's Chemical Market Associates, a consulting group, says the area has roughly 107 large-scale petrochemical plants and refineries.Port of Houston web site. Map of Houston chemical, petroleum and other industrial sites (click on pictures to make them bigger):

According to one congressional report, Texas is home to as many as 29 high-risk plants near population centers of 1 million or more — more than twice the number in any other state — and many are along the Ship Channel.

"It is absolutely critical for petrochemical plants to be safe and secure," said Dennis Storemski, director of Houston's Office of Public Safety and Homeland Security. "Federal security standards for the industry would be another way to ensure adequate protection for the neighboring communities."

Legislation currently in a Senate committee would rank the country's 15,000 chemical plants according to risk and would allow the Department of Homeland Security to penalize or even close facilities that do not meet government requirements.

The bill places a premium on physical security measures — like guns, guards and gates — and has been accepted, for the most part, by the chemical industry and the department.

Local firms Lyondell Chemical Co. and Dow Chemical Co. support most of the bill's provisions.

***

Some Senate Democrats, however, maintain that the legislation is insufficient.

Even Sen. Joseph Lieberman, D-Conn ., one of the bill's primary sponsors, plans to toughen the legislation by offering an amendment that would require chemical plants to use less-dangerous chemicals and procedures when possible, a practice known as "inherently safer technology," or IST.

But attempts to require IST are opposed by the influential chemical lobby and the Department of Homeland Security.

***

Chris VandenHeuvel, a spokesman for the American Chemistry Council, an industry group, said that many companies already employ safe technology measures. In late 2001, the council vehemently opposed a security bill that contained IST language. The legislation died on the floor of the Senate.

"It is one of the most unclear concepts out there," VandenHeuvel said. "Nobody knows what it means. Nobody would know what it looks like. Nobody would know how to do it."

No comments:

Post a Comment