One of the great sea mysteries of all time - the loss of USS Cyclops in the "Bermuda Triangle" in 1918 has been offered up as one of the proofs of the Triangle's power...of course, the "Bermuda Triangle" includes some of the most heavily trafficked waters in the world, so the odds of a ship sinking would seem to be higher in high trafffic areas... be that as it may, the Cyclops is a more interesting tale than you might think:

One of the great sea mysteries of all time - the loss of USS Cyclops in the "Bermuda Triangle" in 1918 has been offered up as one of the proofs of the Triangle's power...of course, the "Bermuda Triangle" includes some of the most heavily trafficked waters in the world, so the odds of a ship sinking would seem to be higher in high trafffic areas... be that as it may, the Cyclops is a more interesting tale than you might think:Her specifications and history

(Collier: full load displacement 19,360; length 542'; beam 65'; draft 27'8"; speed 15 knots.; complement 236)Her Master/Captain was an interesting figure:

The...Cyclops, a collier, was launched 7 May 1910 ... and placed in service 7 November 1910, G. W. Worley, Master, Navy Auxiliary Service, in charge. Operating with the Naval Auxiliary Service, Atlantic Fleet, the collier voyaged in the Baltic during May to July 1911 to supply 2d Division ships. Returning to Norfolk, she operated on the east coast from Newport to the Caribbean servicing the fleet. During the troubled conditions in Mexico in 1914 and 1915, she coaled ships on patrol there and received the thanks of the State Department for cooperation in bringing refugees from Tampico to New Orleans.

With American entry into World War I, Cyclops was commissioned 1 May l917, Lieutenant Commander G. W. Worley in command. She joined a convoy for St. Nazaire, France, in June 1917, returning to the east coast in July. Except for a voyage to Halifax, Nova Scotia, she served along the east coast until 9 January 1918 when she was assigned to Naval Overseas Transportation Service. She then sailed to Brazilian waters to fuel British ships in the south Atlantic, receiving the thanks of the State Department and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific. She put to sea from Rio de Janiero 16 February 1918 and after touching at Barbados on 3 and 4 March, was never heard from again. Her loss with all 306 crew and passengers, without a trace, is one of the sea's unsolved mysteries.

Investigations by the Office of Naval Intellegence revealed that Captain Worley was born Johan Frederick Wichmann in Sandstadt, Hanover Province, Germany in 1862, and that he had come to America by jumping ship in San Francisco in 1878. By 1898 he had changed his name to Worley (after a seaman friend), and succeeded in owning and operating a saloon in San Francisco's Barbary Coast. He also got help from brothers whom he had convinced to emigrate. During this time he had qualified to the position of ship's master, and had commanded several civilian merchant ships, picking up and delivering cargo (both legal and illegal; some accounts say opium) from the Far East to San Francisco. Unfortunately, the crews of these ships reported that Worley suffered from a personality akin to HMS Bounty captain William Bligh: the crew was often brutalized by Worley for trivial things.Worley was a bit of a character, you might say:

Naval investigators discovered information from former crewmembers and others about Worley's habits. He would berate and curse officers and men for minor offenses, sometimes getting violent; at one point, he had allegedly chased an ensign about the ship with a gun. Saner times would find him making his rounds about the ship dressed in long underwear and a derby hat.More on the long underwear and hat here:

It was from this incident that Conrad Nervig was to get to know Worley much better than any other of the crew or officers. Nervig recalled that Mr. Cain’s duty had been the mid-watch, the very lonely hours of the night and early morning. He now had to take over these duties. It was during this time that Worley came up from his cabin below the bridge and paid him the first of many visits. They were now in the tropics; the nights were balmy and calm. “I was somewhat startled to see him coming up the starboard ladder dressed in long woolen underwear, a derby hat, and a cane.” Nervig was worried about what he might have done wrong; yet Worley was “affable” and quite indifferent to Nervig’s crisp military salute “Good morning, Captain.” This was, in fact, a social call.However,

For some 2 hours Worley and he leaned on the forward bridge railing while “he regaled me with stories of his home and numerous incidents of his long life at sea. He had a fund of tales, mostly humorous. These nocturnal visits became a regular routine, and I rather enjoyed them. His uniform, if it could be so called, never varied from what he had worn on that first occasion. I have often wondered to what I owed these visits--his fondness for me or his sleeplessness.”

The most serious accusation against Worley was that he was pro-German in war time; indeed, his closest friends and associates were either German or Americans of German descent. ONI contacted the U.S. consul on Barbados, the Cyclops' last port of call. Consul Brockholst Livingston replied in a letter that Worley was "referred to by others as damned Dutchman (for 'Deutch', i.e. German)." "Many Germanic names appear" Livingston continued, hinting that the ship, instead of sinking, may have been handed over to the Germans.[4] One of the passengers on the final voyage was Alfred Louis Moreau Gottschalk, the consul-general in Rio de Janeiro, who was as roundly hated for his pro-German sympathies as was Worley.[5] Speculation within the Navy and the State Department insinuated that Worley and Gottschalk had collaborated together to surrender the ship. After World War I, German records were pored over to ascertain the fate of the Cyclops, whether by Worley's hand or by submarine attack. Nothing was found.One of the telegrams raising concerns about Worley can be found here. The implcation being, of course, that Worley had perhaps turned the ship over to the Germans. No evidence of this was found in post-war searches of German records.

Clive Cussler, the author of sea adventures, many of which involve sunken ships, sponsers an organization devoted to maritime archeology. Its website has much to say about Cyclops here:

Vincent Gaddis and Charles Berlitz have made fortunes touting barrel loads of bull s**t from their books on the mythical triangle while Larry Kusche, a library researcher at the Arizona State, wrote an admirable, in-depth work called "The Bermuda Triangle Mystery - Solved" and barely made beer money.Despite this discovery the mystery wreck has not been relocated and may, in fact, be one of Cyclops's sister ships (we know it's not Jupiter because she was renamed Langley, converted to an aircraft carrier and sunk by the Japanese off Java in WWII).

Kusche has soundly demonstrated that the Cyclops most likely went down between Cape Hatteras and Cape Charles under a heavy gale that struck the east coast on the 9th and 10th of March. During the raging winds and high seas, the ship's cargo of 10,000 tons of manganese probably shifted and she rolled over and sank without warning or time to send an SOS.

***

The Cyclops still remains the largest navy ship ever lost without leaving the slightest clue to her fate.

Interesting when you think about it. The only difference between a great sea mystery and a perfectly explainable ship sinking is one survivor.

No clue turned up until 1968 when master navy diver, Dean Hawes, descended on a large hulk lying in 180 feet of water about 40 nautical miles northeast of Cape Charles. Hawes was stunned. He found himself standing on a vessel unlike any he'd ever seen. The bridge sat on steel stilts above the deck and huge arms stretched upward along the main deck into the liquid gloom.

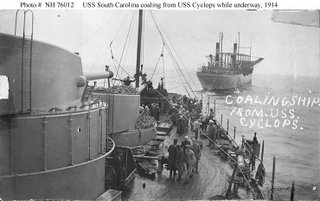

One more interesting aspect of Cyclops (especially for an old service force sailor) is that she was used to experiment with refueling at sea, as set out here in the description of the adjacent photo:

USS South Carolina (BB-26)and USS Cyclops (1910-1918)-Engaged in an experimental coaling while under way at sea in 1914. Rigging between the two ships was used to transfer two 800-pound bags of coal at a time. The bags were landed on a platform in front of the battleship's forward 12-inch gun turret, and then carried to the bunkers.

The donor, who served as a seaman in South Carolina at the time, comments: "it showed that this was possible but a very slow method of refueling. Nothing was heard of the test afterwards."

Whatever happened to Cyclops, she took all her crew with her and, today, we salute them.

Whatever happened to Cyclops, she took all her crew with her and, today, we salute them.UPDATE: A note on "The Bermuda Triangle" from here:

The Bermuda Triangle is a best-selling 1974 book by Charles Berlitz which popularized the belief of the Bermuda Triangle as an area of ocean prone to disappearing ships and airplanes. The book sold nearly 20 million copies in 30 languages.[1]UPDATE2: Kusche also has critics, as found here:

In the book, Berlitz lists several theories for the purported disappearances, although he only gives credence to theories that have natural background.

The book was the subject of criticism in Larry Kusche's 1975 work The Bermuda Triangle Mystery—Solved, in which Kusche cites errors in the reports of missing ships. [2] Lloyd's of London has determined the Triangle to be no more dangerous than any other piece of the ocean, and does not charge unusual rates of insurance for passage through the area. Coast Guard records confirm this determination. However, tales of missing ships, although promoted by Berlitz, existed prior to the book's publication.

Kusche is all over the place concerning this great mystery, but seems completely ignorant of the sobering records extant at the National Archives. As such he seems to credit Conrad Nervig’s story, though the officer list at the NARA shows no Nervig. But we are now coming to some of the most famous mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle. Kusche seems to feel the pressure to solve one categorically. In doing so, he makes one comment that could make Ripley sit up and blink. “I confidently decided that the newspapers, the Navy, and all the ships at sea had been wrong, and that there had been a storm near Norfolk that day strong enough to sink the ship.” On top of this, he writes: “Contrary to popular opinion, there never was an official inquiry into the disappearance . . .Had there been any investigation, the weather information would surely have been discovered.”More on the Bermuda Triangle at Bermuda-Triangle.org, run by Gian Quasar. The portion of the somewhat chaotic website dealing with Cyclops is here.

The Cyclops is perhaps the most investigated case of the US Navy, lasting some 10 years. Anything being reported was still to be directed to ONI even this long afterward. There was no storm. The original weather logs are even in the documentation, which amounts to 1,500 pages in boxes 1068-1070 at the Modern Military Branch at the NARA. What is peculiar is that in Kusche’s bibliography he makes note of very select records there, but not to all the documentation available. Certainly, “research” required examining it all, especially NARA records? The Cyclops remains, as the Navy calls it, “the greatest mystery in the annals of the Navy” though Kusche feels “the missing missing part of the puzzle, a substantial reason for the disappearance, has finally been found—the overlooked storm of March 10.” His “storm” is the only thing missing.

P.S. The Cyclops was not due at Baltimore until the 13th and was therefore no where near Kusche’s “storm” of March 10 off the Virginia Capes. Kusche never even mentions an ETA date in his whole recital. Strange.

My book, U.S.S. CYCLOPS was published late last year by Heritage Books, Inc. (ISBN: 0788451863).

ReplyDeleteThis was the result of 13 years of research. My great uncle was a fireman assigned to the ship. He was among the 309 lost when the collier disappeared. I believe that the book will help to dispel many of the myths and mystery surrounding the ship.

I have been speaking about the ship. A complete schedule of public events may be found at: http://mysite.verizon.net/vzez3ezf/

The personnel listings in the book document the more than 1,600 men who served on board the collier from 1910-1918. Additionally, it contains the only accurate list of the crew and passengers at the time of the ship's disappearance. It also documents the fact that the Navy's 1920 book of those lost during the World War was incomplete. Those missing names are accounted for in my book. A list of purposes for those traveling on the Cyclops is also included. Also contains over 2,300 footnotes with explanations / sources.

I hope that this information helps those interested in researching the vessel, her crew, and passengers. I would be glad to respond to inquiries at cyclops.book@gmail.com .

- Marvin Barrash

In April 1918 The washington Times had a report of the last sighting of the Cyclops by the Amoloco http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-04-19/ed-1/seq-11/#words=Amolco&date1=1918&rows=20&searchType=basic&state=&date2=1918&proxtext=Amolco+&y=12&x=14&dateFilterType=yearRange&index=0

ReplyDeleteIn 1929 Popular Science article reports that indeed the Cyclops was probably lost in a storm at sea in 1918

http://books.google.com/books?id=XSgDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA15&dq=Popular+Science+1931+plane&hl=en&ei=XeARTe7ZJ4alnQf84KjpDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAzgU#v=onepage&q&f=true