In last week's Sunday Ship History, the discussion centered around the ability of a ship's captain to pull his ship alongside an enemy's vessel to put his guns into range and allow them to be aimed at the opponent's ship. For the most part, aiming guns in ships with port and starboard guns was done by pointing the ship and only one side could be engaged at a time.

In last week's Sunday Ship History, the discussion centered around the ability of a ship's captain to pull his ship alongside an enemy's vessel to put his guns into range and allow them to be aimed at the opponent's ship. For the most part, aiming guns in ships with port and starboard guns was done by pointing the ship and only one side could be engaged at a time. A “broadside” was defined by having all the guns on one side of the ship brought to bear at once. In order to bring the guns on the unengaged side to bear, the ship had somehow get to the other side of the attacked ship or, if able, run ahead of the opposing ship and turn about and run back down the same side it had attacked. Otherwise only about half of its guns could be used to fight another ship. The idea was to get close, fire several volleys and then smack into the other ships and engage in hand to hand battle.

A “broadside” was defined by having all the guns on one side of the ship brought to bear at once. In order to bring the guns on the unengaged side to bear, the ship had somehow get to the other side of the attacked ship or, if able, run ahead of the opposing ship and turn about and run back down the same side it had attacked. Otherwise only about half of its guns could be used to fight another ship. The idea was to get close, fire several volleys and then smack into the other ships and engage in hand to hand battle.Warships were rated by the number of guns they bore and a design balance had to be maintained between speed and the number of guns and their throw weight of projectiles. No matter how many guns, however, with the exception of bow chasers and perhaps some guns pointing astern (limited in both cases by the beam of the ship – a much narrower space then the length of the ship).

And, no matter the number of guns, maneuvering meant everything. Such maneuvering required substantial room for the ships to operate. Battles between large ships in narrow or restricted waters were rare and, almost by necessity, “passing” affairs because there was not simply not enough room to maneuver.This approach to aiming ship's guns by turning the ship essentially began with the first installation of cannon on ships and lasted for centuries.

Even with the addition of steam propulsion, ships continued to mount guns along their sides.

In fact, this approach lasted up until the American Civil War. During that war, the U.S. Navy learned that the innovative Confederate Navy was transforming the capture sloop USS Merrimac into an iron clad, the CSS Virginia.

Cladding a steam powered ship in iron was a terrific threat to the wooden hulled warships then dominating the U.S. Fleet. The Confederates were hopeful that their new ironclad wold help them break the Union blockade of Southern ports (see here).

The Union Navy began looking for a counter to the Rebel threat.

In doing so, it turned to a Swedish immigrant inventor, John Ericsson. Mr. Ericsson came up with a truly revolutionary design – creating a low free board (that the measure of the distance between the main deck of a ship and the surface of the water) ship that would be hard to batter with cannon fire. The tale is well told here.

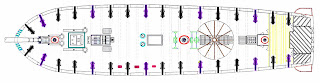

Since the ship was steam powered with a screw, there were almost no masts or paddle wheels to interfere with the aiming of the guns. Ericsson's design was a ship that could engage and enemy ship from virtually any direction. This revolving turret was a great leap forward in war at sea.

Because the turret revolved, the cannon could be aimed by rotating the turret, regardless of the heading of the ship – Ericsson's vision made maneuvering the ship in tight confines like rivers and narrows possible.

Ericsson's creation became, of course, the Monitor, perhaps the most revolutionary ship after Fulton's Claremont and before the first real submarines.

Not surprisingly, the Navy initially rejected the revolutionary design but a competitor helped Ericsson out:

In September 1861, the Ironclad Board, which consisted of Captains Hiram Paulding, Joseph Smith and Charles Davis, recommended that two contracts be let. One went to Cornelius Bushnell of New Haven, Conn., for Galena, and the other to Merrick & Sons, Philadelphia, for New Ironsides. Both were conventional masted and sparred iron-plated broadside warships.Bushnell, vastly impressed with the plans, took them to Secretary of War Welles and to President Lincoln. With such intervention, the "cheese box on a raft" was built in Brooklyn, NY. In March 1862, Monitor was towed to Norfolk, Virginia, just in time for it to confront Virginia, which had also just been completed and had been successful in its first major foray:Ericsson was disappointed and depressed. Then he received an unexpected visitor at his home on Franklin Street: Cornelius Bushnell. Bushnell was concerned because naval authorities doubted whether Galena would be able to carry the stipulated amount of 400 tons of armor on her topsides. Bushnell had been told to consult with Ericsson on the matter.

Ericsson happily received his guest, and advised him on the matter. As Bushnell prepared to leave, Ericsson asked if he was interested to see his own plans for a totally new type of low-draft ironclad warship. Ericsson showed him the latest version of the model of his ‘Cupola Vessel’ and copies of drawings for his proposal to President Lincoln.

The ship looked simple enough, a raft with a gun turret in the middle. Ericsson boasted that it was secure against the heaviest shot and designed for action in shallow coastal waters like Hampton Roads and Southern rivers. He explained that even in narrow passages it could operate its guns in battle, since only the turret needed to be turned.

At dawn on 9 March 1862, CSS Virginia prepared for renewed combat. The previous day, she had utterly defeated two big Federal warships, Congress and Cumberland, destroying both and killing more than 240 of their crewmen. Today, she expected to inflict a similar fate on the grounded steam frigate Minnesota and other enemy ships, probably freeing the lower Chesapeake Bay region of Union seapower and the land forces it supported. Virginia would thus contribute importantly to the Confederacy's military, and perhaps diplomatic, fortunes.

However, as they surveyed the opposite side of Hampton Roads, where the Minnesota and other potential victims awaited their fate, the Confederates realized that things were not going to be so simple. There, looking small and low near the lofty frigate, was a vessel that could only be USS Monitor, the Union Navy's own ironclad, which had arrived the previous evening after a perilous voyage from New York. Though her crew was exhausted and their ship untested, the Monitor was also preparing for action.

Undeterred, Virginia steamed out into Hampton Roads. Monitor positioned herself to protect the immobile Minnesota, and a general battle began. Both ships hammered away at each other with heavy cannon, and tried to run down and hopefully disable the other, but their iron-armored sides prevented vital damage. Virginia's smokestack was shot away, further reducing her already modest mobility, and Monitor's technological teething troubles hindered the effectiveness of her two eleven-inch guns, the Navy's most powerful weapons. Ammunition supply problems required her to temporarily pull away into shallower water, where the deep-drafted Virginia could not follow, but she always covered the Minnesota.

Soon after noon, Virginia gunners concentrated their fire on Monitor's pilothouse, a small iron blockhouse near her bow. A shell hit there blinded Lieutenant John L. Worden, the Union ship's Commanding Officer, forcing another withdrawal until he could be relieved at the conn. By the time she was ready to return to the fight, Virginia had turned away toward Norfolk.

The first battle between ironclad warships had ended in stalemate, a situation that lasted until Virginia's self-destruction two months later. However, the outcome of combat between armored equals, compared with the previous day's terrible mis-match, symbolized the triumph of industrial age warfare. The value of existing ships of the line and frigates was heavily discounted in popular and professional opinion. Ironclad construction programs, already underway in America and Europe, accelerated. The resulting armored warship competition would continue into the 1940s, some eight decades in the future.

The "cheese box" turret lead to improvements in naval guns and allowed development of naval gun that opened the range of warfare at sea from 100 yards to several miles.

The revolution began.

No comments:

Post a Comment