Within a few years of the first flight of a powered aircraft, the U.S. Navy was fully engaged in trying to find ways to use airplanes in combination with ships – for scouting for the fleet, attacking submarines and for engaging in shore attacks. In this pre-aircraft carrier time, planes were launched off platforms rigged on ships, or from experimental catapults mounted on battleship gun turrets.

Within a few years of the first flight of a powered aircraft, the U.S. Navy was fully engaged in trying to find ways to use airplanes in combination with ships – for scouting for the fleet, attacking submarines and for engaging in shore attacks. In this pre-aircraft carrier time, planes were launched off platforms rigged on ships, or from experimental catapults mounted on battleship gun turrets.

Not surprisingly, sea planes were popular with designs based on the works of Glenn Curtiss, as noted here:

Naval aviation's outstanding technical product of the war was the long-distance flying boat. Numerous types appeared but they all bore the look of a single family. The design progressed through the HS-1 and H-16 to the British original known as the F5L, but all could trace their ancestry to the earlier work of Glenn Curtiss. The culmination of work with flying boats in the war was the Curtiss NC type. A product of three Naval constructors, a Yankee builder of aircraft, and New England yacht manufacturers, the NC type became immortal in 1919 as the first aircraft to fly the Atlantic.But, as briefly noted in that article about the rise of the U.S. Naval Aviation community, there was a small side note of history that seems, perhaps, to be reappearing in a couple of new forms.

The flying boat was so impressive that many Naval aviators urged its adoption as the major means of taking air power to sea. Others remained of the opinion that aircraft should fly from the combatant ships of the fleet, and enthusiasts of lighter-than-air pointed to airship success in the war and urged development of their specialty. The logic of these claims, and the usefulness of these aeronautic types, were not ignored. The 1920's saw development in each area. But even as the war ended, sentiment in favor of the aircraft carrier was gaining currency. In 1919, the Navy decided to convert a collier to a carrier. This decision represented a modest beginning for a program which would occupy the attention of a host of ship builders, aircraft designers, and naval tacticians for years to come.

In March of 1919, the U.S. Navy first successfully launched a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft (as opposed to dirigibles, blimps and manned kites) from a self-propelled moving vessel that was not a major ship (H.C. Mustin launched off a moving battleship in 1915):

March 7--In a test at NAS Hampton Roads, Lieutenant (jg) F. M. Johnson launched an N-9 landplane (NB E1 – it was actually an N-9 seaplane) from a sea sled making approximately 50 knots. The sea sled was a powerful motor boat designed to launch an aircraft at a point within range of the target and had been developed experimentally at the recommendation of and under the guidance of Commander H. C. Mustin as a means of attacking German submarine pens.So, one may reasonably ask, “What the heck is a "sea sled’?”

Before delving into that topic completely, it is important to know what the British were up to as they sought solutions to the very troublesome anti-submarine warfare (ASW) issues their island nation was battling. An excellent summary of one approach can be found in Scot McDonald’s “The Aeroplane Goes to Sea” from the Feb 1962 edition of Naval Aviation News (downloadable as a pdf from here):

The British had been mulling over the problem of ASW and in October 1918 proposed a possible solution to it. The proposal, at the sameNow, to get back to the “sea sleds.”time, gave a keen revelation of the effectiveness of its carrier operations. Since most submarine sightings and sinkings (there were few of the latter) made by aircraft were from shore-based seaplanes, the Royal Navy suggested planes be given a much wider range than they enjoyed. They proposed a plan to tow

the planes on lighters or barges to within striking distance of the targets selected. A rear compartment in the barge would be flooded sufficiently to float the plane. The aircraft would then take off, bomb its target and return to home base.

Surprisingly, the plan met with favor. The British volunteered to contribute 50 of the lighter units and asked the U.S. to provide 30, along with 40 planes. By the end of July 1918, the towed-lighter project saw the commissioning of a base at Killingholme, Ireland, with an American detachment in command. In a dress dress rehearsal for the scheduled bombardment of the submarine base at Helgoland, a German zeppelin appeared on the scene and photographed the entire operation. The secret type of attack no longer secret, the British called off the campaign in August.

There was this inventor named Albert Hickman who had an idea about boat hull designs. Sometime before 1914 (we know it was before, because he got a patent in 1914), Mr. Hickman invented a new hull form commonly referred to as “inverted V bottom.”

Up to that time, most hull forms were in the shape of the letter “V”, with the bottom of the V being the part of a hull deepest in the water. Hickman stood that idea on its head, creating a hull shaped more like a “W” – almost a catamaran, but not quite. Down the center line of the hull ran a notch – the notch started off deeper in the bow of the boat and tapered off toward the stern. The effect of this “inverted V” as designed by Hickman was to trap an air bubble under the hull. As speed increased, these Hickman boats would rise up and plane on that air bubble. In doing so, the amount of hull area in contact with the water decreased and such a decrease eliminated substantial amounts of hull drag. This decrease in drag made these boats, dubbed by Mr. Hickman “sea sleds,” fast – very fast for their day. In addition, they were stable and because they rode on a cushion of air, reasonable smooth riding. See here:

A new type of vessel, which promises to revolutionize water craft and which takes the same place on the water that the automobile does on land.’ -- Scientific American Sept. 26, 1914. The Scientific America quote described the Hickman Sea Sled, a radical boat design patented in 1914 by Canadian William Albert Hickman. Eight decades later the design still qualifies as radical.See also this article by Dr. David F. Winkler, a historian with the Naval Historical Foundation:

The hull is an inverted V that resembles a power catamaran, when viewed from the front. But inside, the tunnel the hull sides rise at an angle toward the centerline, creating an upside-down V. Approaching the stern, the V gradually flattens out and slopes down to the waterline, creating a flat bottom at the transom. The design's purpose is to trap air and water, creating lift in the tunnel as the boat moves forward.

The sea sleds' performance exceeded that of any other boat of its era and, arguably any boat of this era. They were far faster and more seaworthy than any other boat and had spectacular load-carrying ability. They were built in every possible form -- as small skiffs, yachts, race boats and military vessels up to 70 feet.

In 1918 Hickman built a 50-foot, high speed torpedo boat in an attempt to convince the Allied navies that a small, fast boat with a huge load-carrying potential could wreck havoc among large slow enemy ships in WWI.

He proved that the boat, with a staggering 56,000 pounds all-up weight, could easily exceed 40 knots. In one test it maintained 34-1/2 knots in a storm with 12-to-14-foot-waves.

Also in 1918, Hickman built the first aircraft carrier in the form of a 55-foot sea sled. The sled carried a Carponi bomber with a 10,000-pound bomb load at 47.75 knots. To launch the bomber, the pilot and the sea sled captain both ran their engines to full throttle. The sea sled would reach 61 mph and the bomber would take flight. Landing on the sea sled was obviously out of the question.

The war ended in 1918, and with it Hickman's involvement with the Navy. After the war he licensed his patents to Sea Sled Corp., which built pleasure boats until the mid '50s.

A major problem confronting allied naval commanders during World War I was the German U-Boat menace. Convoy operations and a North Sea mine barrage helped curtail the threat, but the commanders agreed that strikes at German U-Boat facilities at Kiel, Cuxhaven, Wilhelmshaven, and Heligoland Island could truly set back the German undersea effort. But how? Minefields, shore fortifications, as well as a fleet of modern warships canceled out a raid by allied surface combatants. Also, the enemy facilities were beyond the range of allied bombers based in France and England.Here’s a slightly different version of the tale, from the bio of Mr. Hickman:

Rear Adm. William S. Sims, commander of U.S. Naval Forces in Europe, welcomed suggestions. One proposal for a ferryboat to carry seaplanes to within striking distance morphed into a concept where seaplanes would be ferried using towed lighters. The problem was that seaplanes needed fairly calm seas for liftoff and could not carry much ordnance. The North Sea rarely offered idyllic flying conditions for seaplanes.

Enter Cmdr. Henry C. Mustin, assigned at the time to the battleship USS North Dakota. Responding to a message sent out by Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels calling for "war-winning" ideas, Mustin, a proponent for using aircraft offensively, proposed that aircraft be launched from fast, motorized sea sleds. To cripple the German naval infrastructure, Mustin envisioned 2,800 of these sleds, launching a variety of scout planes, fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes.

By December 1917, the proposal had won the approval of the Navy's first Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. William S. Benson, as well as the British Admiralty. Mustin received orders to report to the Bureau of Construction and Repair in Washington, D.C., to oversee the project. Mustin quickly established a timetable to have the units in place to launch strikes in the spring of 1919.

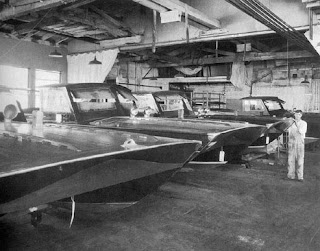

Murray & Tregutha won the contract to design and build the sleds. Caproni, an Italian aircraft manufacturer, received the contract to build the aircraft. Murray & Tregutha delivered the first two sea sleds in the fall of 1918 and Mustin acquired a Caproni Ca.5 bomber from the Army to begin sea trials. Powered by four 450-HP engines, the sleds achieved speeds approaching 50 knots. With the aircraft attached and its engine running, the sleds exceeded that.

Unfortunately, on a sea trial conducted on Nov. 15, 1918, the release mechanism on the Caproni aircraft did not disengage and the trial was a failure. However, during the following spring, using a Curtis N-9 seaplane piloted by Lt. j.g. F. M. Johnson, USNR, Mustin demonstrated the viability of the concept. Of course, by this time the war was over and production plans had been canceled. Rather than sea sleds, the Navy would turn to another larger vessel to launch aircraft: the aircraft carrier.

Mustin's efforts were not for naught though. As World War II approached, the Navy sought designs for fast motor torpedo boats. The old sea sled plans were dusted off and features were incorporated into what became the famed World War II PT Boat.

Impressed by the Sea Sled's smooth ride and stability, Mustin suggested to the Navy that they contract Hickman to build a high-speed aircraft carrier. His idea was to increase the range of heavy, land-based bombers attacking Germany by launching them from Sea Sleds in the Zuider Zee.See also Mustin: A Naval Family of the 20th Century by John Fass Morton, excerpts of which are available here, with pages 112-115 particularly relevant, especially the paragraph that reads:

Someone in the Navy Department bought the idea, and by early 1918 Hickman had designed and the Murray & Tregurtha Yard built two 25-ton, 55' prototypes. Using only 1.800 hp, they made 55 mph with a 10,000-lb Caproni bomber on board. With the bomber's engines racing, they could make even higher speeds, which were enough to successfully effect a launch.

These boats were Hickman's masterpieces, and they probably took the Sea Sled form to its most effective conclusion. They incorporated the first use (backed by international patents) of planing sponsons, lifting strakes, bevelled (non-tripping) chines, and many other details that were to find their way into his future boats---and into those of other designers.

The 11 November 1918 armistice closed the book on Mustin’s operation, but the research community did not forget the sleds.About 6,000 Sea Sled design boats were built, many of them

***

Naval architect George F. Crouch, who received $15,000 in 1939 from the Navy for a V-bottom design, said, “the Sea Sled type ofconstruction is superior to that of V bottom boat in speed, riding qualities and weight carrying ability.”

serving a nice yachts or powerboats.

serving a nice yachts or powerboats.At least one Navy sea sled was a named vessel, USS Bab.

Much more on the “sea sleds” here including some excellent pictures.

Many of you will be more familiar with a hull developed as a spin-off of the Sea Sled design – the now classic Boston Whaler hull. As set out here, the Boston Whaler was designed as an improvement on the Hickman design:

Back in the 1920's a Nova Scotian named Hickman had designed a novel boat called the Sea Sled. Unlike traditional boats, the Sea Sled had two widely separatedThe Boston Whaler is not the last boat builder to use concepts developed by Hickman.hulls or "runners" and was blunt bowed. In Hunt's view, the Sea Sled had never been properly exploited. So his initial design for Fisher was very similar to a Sea Sled.

Using epoxy and styrofoam, Fisher soon built a prototype of Hunt's design. "It had two keels," said Fisher, "one inverted V [between the runners] and an anti-skid, anti-trip chine." Powering it with a 15-hp outboard, Fisher ran the boat all summer, thinking it "the greatest thing ever."

When rougher weather came in the fall, a flaw in the new design was revealed. When under heavy load and plowing along below planning speeds, the middle cavity in the hull forced air into the water as it rushed into the propeller. This lead to partial cavitation and rough running for the motor.

Fisher took his problem to the originator of the Sea Sled, Hickman himself, but this consultation held little hope for improvement. Hickman was certain the Sea Sled was the way to go and offered no modifications.

Fisher decided that they'd have to "put some stuff on the bottom to move that airy water out the there." Development took place at his home, located on a tidal marsh. "We'd take the boat down and put fiberglass things on the bottom at nine o'clock in the morning. Then we would wait until the fiberglass cured and run the boat and find out it didn't work and bring it back and start over again. We'd get maybe three experiments done in one day."

As his experiments evolved, the prototype boat began to have a growing appendage down the center, filling the space between the two runners until it dropped down aft to become a slightly veed bottom. At some point, Fisher called Hunt to come over and see the modified prototype.

Hunt went back to the drawing board, and produced a new design which would ultimately evolve into the 13-foot Whaler. The new hull had a third element between the two runners, projecting down and ending with a nine-inch flat bottom sole in the middle. Fisher, confident that they were on the right track, built a second prototype, this one finished well enough that it could serve as the plug for a production mold.

On sea trials, which consisted of running the new boat full throttle from Cohasset, Massachusetts to New Bedford and back (a distance of 120 miles), Fisher found a new flaw: the boat was "wetter than hell." "A lot wetter," he said, "than the other boat had been." It was the nine-inch wide sole that was throwing all the water and would have to be changed.

But a female mold had already been constructed from the new prototype. Instead of modifying the prototype hull and re-testing, Fisher was so certain he had the right correction he modified the mold! Material was added to transform the flat center section into a vee-bottom, creating more or less of a "pointed keel" in Fisher's words.

From that mold in the fall of 1956 came the Boston Whaler 13 foot hull. And since then the lines of the hull have remained virtually unchanged. The boat that resulted had good stability and excellent load carrying capacity, two attributes that were expected from the hull form, but it also had unexpectedly good performance and handling in rough weather conditions. And its light weight and shape were easily driven by the comparatively low horsepower outboard motors of the time.

Remember, in 1958 a 25 horsepower outboard was a big outboard. In total, it was a design breakthrough.

In many ways, the M Ship Stiletto with its “M Hull Technology” appears to be a throw back to the Sea Sled and its “bubble of air”:

In many ways, the M Ship Stiletto with its “M Hull Technology” appears to be a throw back to the Sea Sled and its “bubble of air”:

Captured air hulls, and the M-hull design in particular, offer less drag and hence greater operating efficiency. These designs may overcome the limitations of conventional hull forms and allow ships to perform over a broader range of operating conditions and missions.

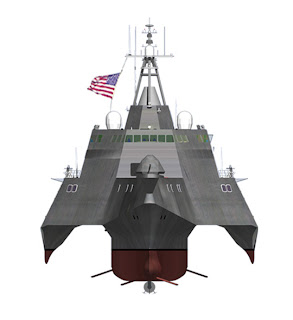

Speaking of other adaptions, the article mentioned above by Dr. Winkler also connects the “sea sleds” with the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship, since his article it titled, “WWI Prototypes Marked Origin of Littoral Combat Ship” and begins:

Speaking of other adaptions, the article mentioned above by Dr. Winkler also connects the “sea sleds” with the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship, since his article it titled, “WWI Prototypes Marked Origin of Littoral Combat Ship” and begins: The Navy currently is developing the Littoral Combat Ship to meet its requirement for a craft that can travel at high speed, have a minimal draft to operate within the littoral, evade minefields, and deliver fire to destroy enemy targets. The origins of this radical new multi-mission ship, however, date back to an initial - and equally radical - attempt to meet those same requirements during World War I.

By the way, the concept of launching sea planes from a towed sled has been revived, too, by a company making UAV’s that can be launched by ships with limited deck space. See here.

By the way, the concept of launching sea planes from a towed sled has been revived, too, by a company making UAV’s that can be launched by ships with limited deck space. See here.Some additional information here.

There are free designs for a inverted V homemade sail/motor boat available here.

More on what happened to the Sea Sled Company here.

I Own A One Of A Kind 1981 55" Hickman Sea Sled & Love It .facebook.com/pages/Hickman-Sea-Sled-Boats/171981839516488 The Original Version Of My Boat Was The 1917 First U.S. Aircraft Carrier It Had A Bi Plane On The Bow (with the plane's engine engaged also) The Plane Would Then Take Off Drop Bombs On Enemy Subs And Fly Back To The Shore (The Boats For Sale ) Make An Offer On The FB Site Thanks

ReplyDelete